I. Whistleblower Investigations

OSHA’s Whistleblower Protection Program enforces the whistleblower provisions of more than twenty-one whistleblower statutes protecting employees who report violations of various workplace safety, airline, commercial motor carrier, consumer product, environmental, financial reform, food safety, health insurance reform, motor vehicle safety, nuclear, pipeline, public transportation agency, railroad, maritime, and securities laws. Rights afforded by these whistleblower Acts include, but are not limited to, worker participation in safety and health activities, reporting a work related injury, illness or fatality, or reporting a violation of the statutes.

Protection from discrimination means that an employer cannot retaliate by taking “adverse action” against workers, such as: firing or laying off, blacklisting, demoting, denying overtime or promotion, disciplining, denial of benefits, failure to hire or rehire, intimidation, making threats, reassignment affecting prospects for promotion or reducing pay or hours. Almost any action taken by an employer which has a negative effect on the employee’s terms, conditions, or privileges of employment amounts to “adverse action”. DOL authority construing similar whistleblower protection statutes indicates that “adverse action” also includes harassment, transfer to a less desirable position and even a change of office location.

Since passage of the OSH Act in 1970, Congress has expanded OSHA’s whistleblower authority to protect workers from discrimination under twenty-one federal laws. (See infra for the list of Acts covered). Complaints must be reported to OSHA within set timeframes following the discriminatory action, as prescribed by each law. “Protecting workers who identify wrongdoing is an essential cornerstone of the U.S. Department of Labor’s worker protection enforcement efforts,” said Secretary Solis. “The members of the whistleblower committee, who represents the interests of labor, management and the public, will utilize their expertise to provide valuable advice and recommendations to help OSHA strengthen and improve our whistleblower protection program.”

Of course, the OSH Act is the principal law protecting whistleblowers. Under §11(c) of the Act, any “person: (who may be an employee, prospective employee, former employee, supervisor, or an employee of someone other than the discriminator) may file a complaint with OSHA (or IOSHA) alleging that he or she suffered work-related discrimination as a result of engaging in protected activity.”

Protected activity under §11(c) includes such things as filing a complaint of unsafe conditions with OSHA or participating in an OSHA inspection as a walk-around participant. It also may include filing a complaint of unsafe conditions with another government agency as well as making a complaint of unsafe conditions directly to the employer. If an employee makes a complaint of unsafe conditions to his or her employer, and the employer does not address the complaint to the employee’s satisfaction, the employer may have to face a refusal by the employee, or employees, to perform the allegedly unsafe work.

OSHA recognizes a limited right of employees to refuse to perform unsafe work if (a) the refusal is made in good faith and with no other reasonable alternative available, (b) the condition the employee believes to be unsafe must be such that a reasonable person, under the same circumstances then confronting the employee, would conclude there is a real danger of death or injury, (c) because of the urgency of the situation, there is insufficient time to eliminate the hazard by complaining to OSHA and, (d) the employee, when possible, must have requested from the employer, but not obtained, a correction of the condition. The right to refuse work under §11(c) is the exception, not the rule. It does not require an employee to be paid for any non-work time due to a work refusal, and the employer may require the employee to perform safe alternative work even if the employee lawfully refuses an unsafe assignment.

II. RECENT OSHA WHISTLEBLOWER ACTIVITY

7/18/2013 - Massachusetts commercial motor carrier and its owner ordered to reinstate a fired employee and pay him more than $131,000 in back wages and damages for terminating him for refusing to drive hours in excess of the maximum daily limit.

4/24/2013 –Feds say Metra whistleblower is owed thousands after dismissal

03/26/2013-OSHA orders Georgia based company to reinstate, pay more than $190,000 to terminated whistleblower in Illinois.

02/28/2013 - Railroad ordered by US Labor Department to pay more than $309,000 for violating the Federal Railroad Safety Act.

02/28/2013 - Railway Co. ordered by US Labor Department's OSHA to pay $1.1 million after terminating 3 workers for reporting injuries.

02/06/2013 - US Department of Labor sues construction company in Florida for firing employee who reported workplace violence.

01/31/2013 - US Department of Labor files whistle-blower lawsuit against Montana based company.

11/29/2012- Railway Co. ordered by US Labor Department to pay more than $288,000 for violating Federal Railroad Safety Act.

11/07/2012 - Illinois flight center ordered by US Labor Department's OSHA to reinstate, pay more than $500,000 to illegally terminated pilot.

III. THE OSHA WHISTLEBLOWER INVESTIGATIONS MANUAL

OSHA Directive Number: CPL 02-03-003, effective September 20, 2011, implements the OSHA Whistleblower Investigations Manual, and supersedes the August 22, 2003 Instruction. This manual outlines procedures, and other information relative to the handling of retaliation complaints under the various whistleblower statutes delegated to OSHA and may be used as a ready reference. Regional Administrators have overall responsibility for the investigation of retaliation complaints under Section 11(c). They have authority to dismiss non-meritorious complaints (absent withdrawal), approve acceptable withdrawals, and negotiate settlement of meritorious complaints or recommend litigation to the Solicitor of Labor in such cases.

In addition to the overall responsibility of enforcing Section 11(c) of the Act, the Secretary of Labor has delegated to OSHA the responsibility for investigating claims of retaliation filed by employees under the whistleblower provisions of the following twenty statutes, which together constitute the whistleblower protection program:

- Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act (AHERA), 15 U.S.C. §2651.

- International Safe Container Act (ISCA), 46 U.S.C. §80507.

- Surface Transportation Assistance Act (STAA), 49 U.S.C. §31105.

- Clean Air Act (CAA), 42 U.S.C. §7622.

- Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), 42 U.S.C. §9610.

- Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA), 33 U.S.C. §1367.

- Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), 42 U.S.C. §300j-9(i).

- Solid Waste Disposal Act (SWDA), 42 U.S.C. §6971.

- Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), 15 U.S.C. §2622.

- Energy Reorganization Act (ERA), 42 U.S.C. §5851.

- Wendell H. Ford Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the 21st Century (A1R21), 49 U.S.C. §42121

- Corporate and Criminal Fraud Accountability Act, Title VIII of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), 18 U.S.C. §1514A (SOX).

- Pipeline Safety Improvement Act (PSIA), 49 U.S.C. §60129.

- Federal Railroad Safety Act (FRSA), 49 U.S.C. §20109.

- National Transit Systems Security Act (NTSSA), 6 U.S.C. §1142.

- Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA), 15 U.S.C. §2087.

- Affordable Care Act (ACA), 29 U.S.C. §218C.

- Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 (CFPA), Section 1057 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, 12 U.S.C. §5567.

- Seaman's Protection Act, 46 U.S.C. §2114 (SPA), as amended by Section 611 of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2010, P.L. 111-281.

- FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), 21 U.S.C. §399d.

A. Whistleblower Complaints

Any applicant for employment, employee, former employee, or his or her authorized representative is permitted to file a whistleblower complaint with OSHA. No particular form of complaint is required. A complaint under any statute may be filed orally or in writing. If the complainant is unable to file the complaint in English, OSHA will accept the complaint in any language. Although the implementing regulations for a few of the whistleblower statutes indicate that complaints must be filed “in writing,”[1] that requirement is satisfied by OSHA’s longstanding practice of reducing all orally-filed complaints to writing.[2]

OSHA, AHERA, and ISCA complaints that set forth a prima facie allegation and are filed within statutory time limits must be docketed for investigation. OSHA, AHERA, and ISCA complaints that do not set forth a prima facie allegation, or are not filed within statutory time limits may be closed administratively—that is, not docketed—provided the complainant accepts this outcome. Complaints filed under STAA, CAA, CERCLA, FWPCA, SDWA, SWDA, TSCA, ERA, AIR21, SOX, PSIA, NTSSA, FRSACPSIA, ACA, CFPA, or FSMA that are either untimely or do not present a prima facie allegation, may not be "screened out" or closed administratively. Complaints filed under these statutes must be docketed and a written determination issued, unless the complainant, having received an explanation of the situation, withdraws the complaint.

B. Timeliness

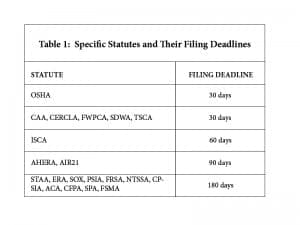

Whistleblower complaints must be filed within specified statutory time frames (see Table 1) which generally begin when the adverse action takes place. The first day of the time period is the day after the alleged retaliatory decision is both made and communicated to the complainant. Generally, the date of the postmark, facsimile transmittal, e-mail communication, telephone call, hand-delivery, delivery to a third-party commercial carrier, or in-person filing at a Department of Labor office will be considered the date of filing. If the postmark is absent or illegible, the date filed is the date the complaint is received. If the last day of the statutory filing period falls on a weekend or a federal holiday, or if the relevant OSHA .Office is closed, then the next business day will count as the final day.

Complaints filed after these deadlines will normally be closed without further investigation. However, there are certain extenuating circumstances that could justify tolling these statutory filing deadlines under equitable principles. (STAA, ERA, CAA, CERCLA, FWPCA, SDWA, SWDA, TSCA, AIR21, SOX, PSIA, FRSA, NTSSA, CPSIA, ACA, CFPA, SPA, and FSMA complaints may not be administratively closed. If the complainant does not withdraw, a dismissal must be issued if the complaint was untimely and there was no valid extenuating circumstance.)

The following are reasons that may justify the tolling of a deadline, and an investigation must ordinarily be conducted if evidence establishes that a late filing was due to any of them. However, these circumstances are not to be considered all-inclusive, and the reader should refer to appropriate regulations and current case law for further information.

-

- The employer has actively concealed or misled the employee regarding the existence of the adverse action or the retaliatory grounds for the adverse action in such a way as to prevent the complainant from knowing or discovering the requisite elements of a prima facie case, such as presenting the complainant with forged documents purporting to negate any basis for supposing that the adverse action was relating to protected activity. Mere misrepresentation about the reason for the adverse action is insufficient for tolling.

- The employee is unable to file within the statutory time period due to debilitating illness or injury.

- The employee is unable to file within the required period due to a major natural or man-made disaster such as a major snow storm or flood. Conditions should be such that a reasonable person, under the same circumstances, would not have been able to communicate with an appropriate agency within the filing period.

- The employee mistakenly filed a timely retaliation complaint relating to a whistleblower statute enforced by OSHA with another agency that does not have the authority to grant relief (e.g., filing an AIR21 complaint with the FAA or filing a STAA complaint with a state plan state).

- The employer’s own acts or omissions have lulled the employee into foregoing prompt attempts to vindicate his rights. For example, when an employer repeatedly assured the complainant that he would be reinstated so that the complainant reasonably believed that he would be restored to his former position tolling may be appropriate. However, the mere fact that settlement negotiations were ongoing between the complainant and the respondent is not sufficient. Hyman v. KD Resources, ARB No. 09-076, AU No. 2009-SOX-20 (ARB Mar. 31, 2010).

Conditions which will not justify extension of the filing period include:

-

- Ignorance of the statutory filing period.

- Filing of unemployment compensation claims.

- Filing of workers’ compensation.

- Filing a private lawsuit.

- Filing a grievance or arbitration action.

- Filing a retaliation complaint with a state plan or another agency that has the authority to grant the requested relief.

C. Amendments to the Complaint

At any time prior to the expiration of the statutory filing period for the original complaint, a complainant may amend the complaint to add additional allegations and/or additional respondents. For amendments received after the statute of limitations for the original complaint has run, the investigator must evaluate whether the proposed amendment (adding subsequent alleged adverse actions and/or additional respondents) reasonably falls within the scope of the original complaint. If the amendment reasonably relates to the original complaint, then it must be accepted as an amendment, provided that the investigation remains open. If the amendment is determined to be unrelated to the original complaint, then it may be handled as a new complaint of retaliation and processed in accordance with the implicated statute.

D. Conduct of the Investigation

The investigator should make clear to all parties that DOL does not represent either the complainant or respondent, and that both the complainant's allegation(s) and the respondent's proffered non-retaliatory reason(s) for the alleged adverse action must be tested. On this basis, relevant and sufficient evidence should be identified and collected in order to reach an appropriate determination of the case. If, having interviewed the parties and relevant witnesses and examined relevant documentary evidence, the complainant is unable to establish the elements of a prima facie allegation, then the case should, be dismissed. In addition, under some of the statutes (ERA, AIR21, STAA, SOX, PSIA, FRSA, NTSSA, CPSIA, ACA, CFPA, and FSMA) even if a complainant has made a prima facie allegation, an investigation of the complaint should not be conducted if the respondent demonstrates, by clear and convincing evidence, that it would have taken the same adverse action in the absence of the complainant's protected activity.

The investigator must ensure that the complainant and the respondent(s) are covered under the statute(s) at issue. Detailed information regarding coverage under each statute can be found in each statute.Some of the statutes may require for coverage purposes that the entity employing the complainant be “engaged in a business affecting commerce” (OSHA 11(c), STAA); “engaged in interstate or foreign commerce” (FRSA); or fulfill similar interstate commerce requirements. The former test is slightly easier to meet than the latter; but under either test, the respondent’s effect on commerce is generally not difficult to establish and is typically not disputed. The use of supplies and equipment from out of state sources, for example, is generally sufficient to show that the business “effects commerce.” See, e.g., United States v. Dye Const. Co., 510 F.2d 78, 83 (10th Cir. 1975).

E. Weighing the Evidence – Burden of Proof

The whistleblower statutes administered by OSHA fall into two groups, with distinct standards of causation and burdens of proof—the "motivating factor" and the "contributing factor" statutes.

-

- “Motivating Factor” Statutes

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (hereinafter 11(c)), the Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act (AHERA), the International Safe Container Act (ISCA), and the six environmental statutes (Safe Drinking Water Act; Federal Water Pollution Control Act; Toxic Substances Control Act; Solid Waste Disposal Act; Clean Air Act; and Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act) require a higher standard of causation – “motivating factor” - and apply the traditional burdens of proof. Under this standard, the investigation must disclose facts sufficient to raise the inference that the protected activity was a motivating factor in the adverse action. The Department of Labor relies on the standards derived from discrimination case law as set forth in Mt. Healthy City School Board v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977) (mixed-motive analysis); Texas Dep't of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248 (1981) (pretext analysis); and McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) (pretext analysis).

The possible outcomes of an investigation of a complaint under a motivating-factor statute are: (1) a preponderance of the evidence indicates that the employer's reason for the retaliation was a pretext, and the complaint is meritorious; (2) a preponderance of the evidence indicates that the employer acted for both prohibited and legitimate reasons (that is, “mixed motives”), and—absent a preponderance of the evidence indicating that the respondent would have reached the same decision even if the complainant hadn't engaged in protected activity, the complaint is meritorious; (3) a preponderance of the evidence indicates that the employer acted for both prohibited and legitimate reasons, but a preponderance of the evidence indicates the respondent would have reached the same decision even in the absence of protected activity, and the complaint must be dismissed; or (4) a preponderance of the evidence indicates that the employer was not motivated in whole or in part by protected activity and the complaint must be dismissed. In mixed-motive cases, the employer bears the risk that the influence of legal and illegal motives cannot be separated.

The Department recognizes the Supreme Court’s decision in Gross v. FBL Financial Services, Inc., 129 S.Ct. 2343 (2009). In that case the Court held that the prohibition against discrimination 'because of age in the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA), 29 U.S.C. §623(a)(1), requires a plaintiff to “prove that age was the ‘but-for’ cause of the employer's adverse decision.” 129 S.Ct. at 2350. The Court rejected mixed motive analysis, i.e., arguments that a plaintiff could prevail in an ADEA case by showing that discrimination was a motivating factor for the adverse decision, after which the employer had the burden of proving that it would have reached the same decision for non-discriminatory reasons. Id. at 2351-52. However, the Department does not believe that Gross affects the long-standing burden-shifting framework applied in mixed-motive cases under 11(c), AHERA, ISCA, and the six environmental whistleblower statutes.

First, Gross involved an age discrimination case under the ADEA, not a retaliation case. The Court cautioned in Gross itself that “[w]hen conducting statutory interpretation, we ‘must be careful not to apply rules applicable under one statute to a different statute without careful and critical examination.” Id. at 2349. Second, the Court based its decision that a mixed motive-analysis was inapplicable to the ADEA in part on its determination that Congress decided not to amend the ADEA to clarify that a mixed-motive analysis applied when it amended both the ADEA and Title VII in the Civil Rights Act of 1991. Negative implications raised by disparate provisions are strongest when the provisions were considered simultaneously when the language raising the implication was inserted. Id. Congress did not consider amendments to the OSHA “motivating factor” statutes when it amended Title VII and the ADEA in the Civil Rights Act of 1991. Thus, these OSHA statutes do not raise the strong negative implications that the Court noted in Gross. Third, in Gross the Court stated that its decision did not undermine prior Supreme Court precedent applying the mixed-motive burden-shifting framework to cases under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). 129 S. Ct. at 2352 n.6 (citing NLRB v. Transportation Management Corp., 462 U.S. 393, 40103 (1983)). The Court in Gross noted that in Transportation Management it had deferred to the interpretation of the NLRA by the National Labor Relations Board. Ibid. Similarly, deference is owed to the reasonable interpretation of the Department of Labor’s Administrative Review Board applying mixed-motive analysis under the environmental whistleblower statutes. Cf. Anderson v. U.S. Department of Labor, 422 F.3d 1155, 1173, 1181 (10th Cir. 2005) (providing Chevron deference to ARB’s construction of I environmental whistleblower statutes). Since Gross was decided, the ARB has continued to apply mixed-motive analysis in environmental whistleblower cases. See, e.g., Abdur-Rahman and Petty v. DeKalb County, 2010 WL 2158226 (DOL. Adm.Rev.Bd. 2010) (Federal Water Pollution Control Act).Gross does not affect pretext analysis under McDonnell Douglas. Geiger v. Tower Automotive, 579 F.3d 614, 622 (6th Cir. 2009) (citing cases).

Recently, in University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar, 12-484, the US Supreme Court held that employees alleging retaliation under Title VII “must establish that his or her protected activity was a ‘but for’ cause of the alleged adverse action by the employer”. The Court rejected the plaintiff’s ‘mixed-motive’ argument.

It remains to be seen what impact the Nassar opinion has on these “motivating factor” statutes. It should be argued that the “but for” analysis applies.

2. "Contributing Factor” Statutes.

The Energy Reorganization Act (ERA), the Wendell H. Ford Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the 21st Century (AIR21), the Surface Transportation Assistance Act (STAA), the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX), the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002 (PSIA), the Federal Railroad Safety Act (FRSA), the National Transit Security System Act (NTSSA), the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (CPSIA), the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 (CFPA), Section 1057 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, 12 U.S.C.A. §5567; Seaman's Protection Act, 46 U.S.C. §2114 (SPA), as amended by Section 611 of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2010, P.L. 111-281; and FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), 21 U.S.C. §399d, require a lower standard to establish causation and a higher standard of proof in order to establish a respondent's affirmative defense. Under these standards, a preponderance of the evidence must indicate that the protected activity was a ‘contributing factor’ in the adverse action. A contributing factor is “any factor, which alone or in combination with other factors, tends to affect in any way the outcome of the decision.” See Marano v. Dep’t of Justice, 2 F.3d 1137, 1140 (Fed. Cir. 1993), 135 Cong.Rec. 5033 (1989). Thus, the protected activity, alone or in combination with other factors, must have affected in some way the outcome of the employer's decision.

The possible outcomes of investigation of a complaint under a contributing-factor statute are: (1) a preponderance of the evidence indicates that protected activity was a contributing factor in the employer's decision, and absent clear and convincing evidence that the respondent would have taken the same adverse action even if the complainant had not engaged in protected activity, the complaint is meritorious; (2) a preponderance of the evidence indicates that protected activity was a contributing factor in the employer's decision, but clear and convincing evidence indicates that the respondent would have taken the same adverse action even in the absence of the protected activity, and the complaint must be dismissed; or (3) a preponderance of the evidence indicates that the protected activity was not a contributing factor in the decision to take the adverse action, and the complaint must be dismissed. In cases where protected activity is not the only factor considered in the adverse action, the employer bears the risk that the influence of legal and illegal motives cannot be separated.

The “contributing factor” statutes also contain “gatekeeping” provisions, which provide that the investigation must be discontinued and the complaint dismissed if no prima facie showing is made. These provisions help stem frivolous complaints and simply codify the commonsense principle that no investigation should continue beyond the point at which enough evidence has been gathered to reach a determination.

F. The Elements of a Violation

An illegal retaliation is an adverse action taken against an employee by a covered entity or individual in reprisal for the employee’s engagement in protected activity. An effective investigation focuses on the elements of a violation and the burden of proof required. If the investigation does not establish, by preponderance of the evidence, any of the elements of a prima facie allegation, the case should be dismissed.

The evidence must establish that the complainant engaged in activity protected by the specific statute(s) under which the complaint was filed. However, with the exception of certain cases involving refusals to work, it is not necessary to prove the referenced statute(s) were actually violated. In other words, the complainant does not need to show that the conduct about which he/she initially complained, for example, wire fraud under SOX, actually took place. Rather, as long as the complainant's protected activity was made in good faith and a reasonable person could have raised the same issue, the action meets this element. Protected activity generally falls into four broad categories:

-

- Providing information to a government agency (including, but not limited to OSHA, FMCSA, EPA, NRC, DOE, FAA, SEC, TSA, FRA, FTA, CPSC, HHS), a supervisor (the employer), a union, health department, fire department, Congress, or the President.

- Filing a complaint or instituting a proceeding provided for by law, for example, a formal complaint to OSHA under Section 8(f).

- Testifying in proceedings such as trials, hearings before the Office of Administrative Law Judges or the OSH Review Commission, or Congressional hearings. And, participating in inspections or investigations by agencies including, but not limited to OSHA, FMCSA, EPA, ERA, NRC, DOE, SEC, FAA, FTA, FRA, TSA, CPSC or HHS.

- Refusal to perform an assigned task. Section 11(c) of the OSH Act, STAA, ERA, NTSSA, FRSA, CPSIA, ACA, and CFPA specifically protect employees from retaliation for refusing to engage in an unlawful work practice. Although the other whistleblower statutes enforced by OSHA do not expressly provide protection for work refusals, the Secretary interprets all of the whistleblower protection statutes enforced by OSHA as providing some protection to employees from retaliation for refusing to engage in certain unlawful work practices. Generally, a worker may refuse to perform an assigned task when he or she has a good faith, reasonable belief that working conditions are unsafe or unhealthful, and he or she does not receive an adequate explanation from a responsible official that the conditions are safe.

The investigation must show that a person involved in the decision to take the adverse action was aware, or suspected, that the complainant engaged in protected activity. For example, one of the respondent's managers need not have specific knowledge that the complainant contacted a regulatory agency if his or her previous internal complaints would cause the respondent to suspect a regulatory action was initiated by the complainant. Also, the investigation need not show that the person who made the decision to take the adverse action had knowledge of the protected activity, only that someone who provided input that led to the decision had knowledge of the protected activity.

If the respondent does not have actual knowledge, but could reasonably deduce that the complainant filed a complaint, it is referred to as inferred knowledge. Examples of inferred knowledge include, but are not limited to:

-

- An OSHA complaint is about the only lathe in a plant, and the complainant is the only lathe operator.

- A complaint is about unguarded machinery and the complainant was recently injured on an unguarded machine.

- A union grievance is filed over a lack of fall protection and the complainant had recently insisted that his foreman provide him with a safety harness.

- Under the small plant doctrine, in a small company or small work group where everyone knows each other, knowledge can also be attributed to the employer.

The evidence must demonstrate that the complainant suffered some form of adverse action initiated by the employer. An adverse action may occur at work; or, in certain circumstances, outside of work. Some examples of adverse actions may include, but are not limited to:

-

- Discharge

- Demotion

- Reprimand

- Harassment - unwelcome conduct that can take the form of slurs, graffiti, offensive or derogatory comments, or other verbal or physical conduct. This type of conduct becomes unlawful when it is severe or pervasive enough to create a work environment that a reasonable person would consider intimidating, hostile, or abusive.

- Hostile work environment - separate adverse actions that occur over a period of time, may together constitute a hostile work environment, even though each act, taken alone, may not constitute a materially adverse action. Courts have defined a hostile work environment as an ongoing practice, which, as a whole, creates a work environment that would be intimidating, hostile, or offensive to a reasonable person. A complaint need only be filed within the statutory timeframe of any act that is part of the hostile work environment, which may be ongoing.

- Lay-off

- Failure to hire

- Failure to promote

- Blacklisting

- Failure to recall

- Transfer to different job

- Change in duties or responsibilities

- Denial of overtime

- Reduction in pay

- Denial of benefits

- Making a threat

- Intimidation

- Constructive discharge - the employer deliberately created working conditions that were so difficult or unpleasant that a reasonable person in similar circumstances would have felt compelled to resign.

It may not always be clear whether the complainant suffered an adverse action. The employer may have taken certain actions against the complainant that do not qualify as “adverse,” in that they do not cause the complainant to suffer any material harm or injury. To qualify as an adverse action, the evidence must show that a reasonable employee would have found the challenged action “materially adverse.” Specifically, the evidence must show that the action at issue might have dissuaded a reasonable worker from making or supporting a charge of retaliation.[3] The investigator may test for material adversity by interviewing coworkers to determine whether the action taken by the employer would likely have dissuaded other employees from engaging in protected activity.

A causal link between the protected activity and the adverse action must be established by a preponderance of the evidence. Nexus cannot always be demonstrated by direct evidence and may involve one or more of several indicators such as animus (exhibited ill will) toward the protected activity, timing (proximity in time between the protected activity and the adverse action), disparate treatment of the complainant in comparison to other similarly situated employees (or in comparison to how the complainant was treated prior to engaging in protected activity), false testimony or manufactured evidence.

Questions that assist in testing the respondent’s position include:

-

- Did the respondent follow its own progressive disciplinary procedures as explained in its internal policies, employee handbook, or collective bargaining agreement?

- Did the complainant's productivity, attitude, or actions change after the protected activity?

- Did the respondent discipline other employees for the same infraction and to the same degree?

G. The Investigation

Personal interviews and collection of documentary evidence must be conducted on-site whenever practicable. Investigations should be planned in such a manner as to personally interview all appropriate witnesses during a single site visit. The respondent’s designated representative has the right to be present for all interviews with currently-employed managers, but interviews of non-management employees are to be conducted in private. The witness may, of course, request that an attorney or other personal representative be present at any time. In limited circumstances, witness statements and evidence may be obtained by telephone, mail, or electronically.

If an interview is recorded electronically, the investigator must be a party to the conversation, and it is OSHA’s policy to have the witness acknowledge at the beginning of the recording that they understand that the interview is being recorded. See 18 U.S.C. § 2511(2)(c). This does not apply to other audio or video recordings supplied by the complainant or witnesses.

The investigator must attempt to interview the complainant in all cases. The investigator must arrange to meet with the complainant as soon as possible to conduct an interview regarding the complainant's allegations. When practical and possible, the investigator will conduct face-to-face interviews with complainants. It is highly desirable to obtain a signed interview statement from the complainant during the interview. A signed interview statement is useful for purposes of case review, subsequent changes in the complainant's status, possible later variations in the complainant's account of the facts, and documentation for potential litigation. The complainant may, of course, have an attorney or other personal representative present during the interview, so long as the investigator has obtained a signed “designation of representative” form.

The investigator must attempt to obtain from the complainant all documentation in his or her possession that is relevant to the case. Relevant records may include, but are not limited to:

-

- Copies of any termination notices, reprimands, warnings or personnel actions.

- Performance appraisals.

- Earnings and benefits statements.

- Grievances.

- Unemployment benefits, claims and determinations.

- Job position descriptions.

- Company employee and policy handbooks.

- Copies of any charges or claims filed with other agencies.

- Collective bargaining agreements.

- Arbitration agreements.

- Medical records. Because medical records require special handling, investigators should familiarize themselves with the requirements of OSHA Instruction CPL 02-02-072, Rules of agency practice and procedure concerning OSHA access to employee medical records, August 22, 2007.

The restitution sought by the complainant should be ascertained during the interview. If discharged or laid off by the respondent, the complainant should be advised of his or her obligation to seek other employment and to maintain records of interim earnings. Failure to do so could result in a reduction in the amount of the back pay to which the complainant might be entitled in the event of settlement, issuance of merit findings and order, or litigation. The complainant should be advised that the respondent’s back pay liability ordinarily ceases only when the complainant refuses a bona fide, unconditional offer of reinstatement. The complainant should also retain documentation supporting any other claimed losses resulting from the adverse action, such as medical bills, repossessed property, etc.

In many cases, following receipt of OSHA’s notification letter, the respondent forwards a written position statement, which may or may not include supporting documentation. Assertions made in the respondent's position statement do not constitute evidence, and generally, the investigator must still contact the respondent to interview witnesses, review records and obtain documentary evidence, or to further test the respondent's stated defense. At a minimum, copies of relevant documents and records should be requested, including disciplinary records if the complaint involves a disciplinary action.

If the respondent requests time to consult legal counsel, the investigator must advise him or her that future contact in the matter will be through such representative. A Designation of Representative form should be completed by the respondent's representative to document his or her involvement. In the absence of a signed Designation of Representative, the investigator is not bound or limited to making contacts with the respondent through any one individual or other designated representative (e.g., safety director). If a position letter was received from the respondent, the investigator's initial contact should be the person who signed the letter.

The investigator should interview all company officials who had direct involvement in the alleged protected activity or retaliation and attempt to identify other persons (witnesses) at the employer’s facility who may have knowledge of the situation. Witnesses must be interviewed individually, in private, to avoid confusion and biased testimony, and to maintain confidentiality. Witnesses must be advised of their rights regarding protection under the applicable whistleblower statute(s), and advised that they may contact OSHA if they believe that they have been subjected to retaliation because they participated in an OSHA investigation.

If the respondent has designated an attorney to represent the company, interviews with management officials should ordinarily be scheduled through the attorney, who generally will be afforded the right to be present during any interviews of management officials. Respondent’s attorney generally does not, however, have the right to be present, and should not be permitted to be present, during interviews of non-management or non-supervisory employees. Any witness may, of course, have a personal representative or attorney present at any time. If the non-management or non-supervisory employee witness requests that Respondent’s attorney be present, the investigator should ask Respondent’s attorney on the record who he/she represents and specifically ask Respondent’s attorney if he/she represents the non-management witness in the matter. It must be made clear to the witness that:

-

- Respondent’s attorney represents Respondent and not the witness; and

- The witness has the right to be interviewed privately.

While at the respondent’s establishment, the investigatorshould make every effort to obtain copies of, or at least review and document in a Memo to File, all pertinent data and documentary evidence which respondent offers and which the investigator construes as being relevant tothe case.

If at any time during the initial (or subsequent) meeting(s) with respondent officials or counsel, respondent suggests the possibility of an early resolution to the matter, the investigator should immediately and thoroughly explore how an appropriate settlement may be negotiated and the case concluded.

When conducting an investigation under § 11(c) of the OSH Act, AHERA or ACA, subpoenas may be obtained for witness interviews or records. The Agency has two types of subpoenas for use in these cases: A Subpoena Ad Testificandum is used to obtain an interview from a reluctant witness. A Subpoena Duces Tecum is used to obtain documentary evidence. They can be served on the same party at the same time, and the Agency can require the named party to appear at a designated office for production, at Agency costs. Subpoenas Ad Testificandum may specify the means by which the interviews will be documented or recorded (such as whether a court reporter will be present). When drafting subpoenas, the party should be given a short timeframe in which to comply, using broad language like “any and all documents” or “including but not limited to,” and making the investigator responsible for delivery and completion of the service form (see example at the end of this chapter). If the respondent decides to cooperate, the Supervisor can choose to lift the subpoena requirements.

H. Appeal Process

It has been OSHA’s long-standing policy and procedure to provide complainants with the rightto appeal determinations under OSHA 11(c), AHERA, and ISCA, although such appeals are not specifically provided for by statute or regulation. If an 11(c), AHERA, or ISCA complaint is dismissed, the complainant may appeal the dismissal to the Director of OSHA's Directorate of Enforcement Programs (DEP). The request must be made in writing to DEP within 15 calendar days of the complainant's receipt of the region's dismissal letter, with a copy to the RA. This review is not de novo. Rather, a committee constituted of National Office staff (Appeals Committee) reviews the case file and findings for proper application of the law to the facts. If the decision is supported by articulate, cogent, and reliable analysis, the Appeals Committee generally recommends to the Director that the determination stand. The agency-level decision is the final decision of the Secretary of Labor.

The complainant’s and respondent's objections under ERA, CAA, CERCLA, FWPCA, SDWA, SWDA, TSCA, AIR21, SOX, PSIA, FRSA, NTSSA, CPSIA, ACA, CFPA, SPA, and FSMA, are heard de novo before a DOL ALL The expression “hearing de novo” means that the ALJ hearing the case relies only on the evidence presented at the hearing. OSHA (referred to in the regulations as the Assistant Secretary) normally does not participate in the hearings; however, OSHA, represented by SOL, may, at its discretion, participate as a party or amicus curiae before the ALJ or the ARB.

I. Remedies

-

- Reinstatement and Front Pay

Under all whistleblower statutes enforced by OSHA, reinstatement of the complainant to his or her former position is the presumptive remedy in merit cases and is a critical component of making the complainant whole. Where reinstatement is not feasible, such as where the employer has ceased doing business or there is so much hostility between the employer and the complainant that complainant's continued employment would be unbearable, front pay in lieu of reinstatement should be awarded from the date of discharge up to a reasonable amount of time for the complainant to obtain another job. RSOL should be consulted on front pay.

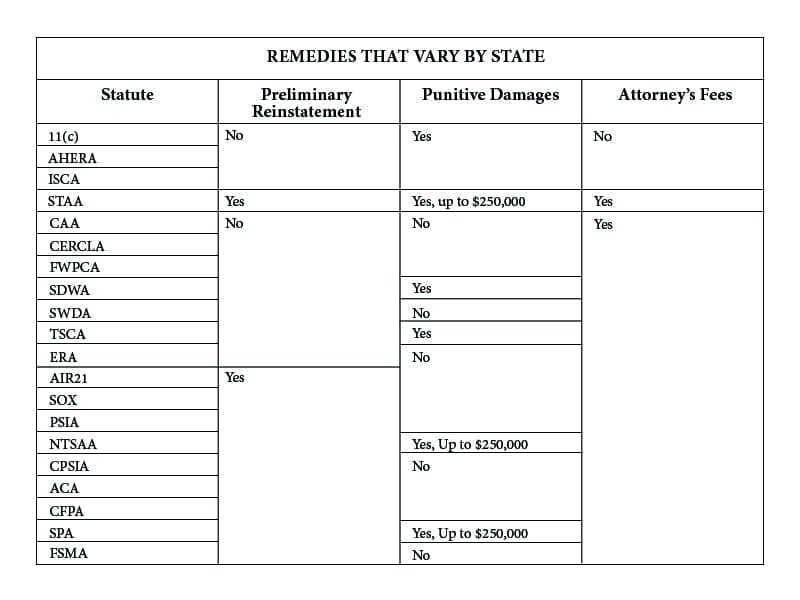

In STAA, AIR21, SOX, PSIA, FRSA, NTSSA, CPSIA, ACA, CFPA, FSMA, and SPA cases involving discharge, where a bona fide offer of reinstatement has not been made, the Assistant Secretary must order immediate, preliminary reinstatement upon finding reasonable cause to believe that a violation occurred. Such a preliminary order may be issued any time after the Assistant Secretary has investigated a retaliation complaint and before issuing a final order (which is achieved after all appeals within the Department of Labor have been exhausted). To ensure respondent's due process rights under the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution, this notification is accomplished and documented by means of a "due process letter." Due process rights are afforded by giving the respondent notice of the substance of the relevant evidence supporting the complainant's allegations as developed during the course of the investigation. This evidence includes any witness statements, which will be redacted to protect the identity of confidential informants where statements were given in confidence; if the statements cannot be redacted without revealing the identity of confidential informants, summaries of their contents will be provided. The letter must also indicate that the respondent may submit a written response, meet with the investigator, and present rebuttal witness statements within 10 days of receipt of OSHA’s letter (or at a later agreed-upon date, if the interests of justice so require). Due process letters must be sent via certified U.S. mail, return receipt requested (or via a third-party commercial carrier that provides delivery confirmation), or via a third-party commercial carrier that provides delivery confirmation.

2. Back Pay

Back pay is available under all whistleblower statutes enforced by OSHA. Back pay is computed by deducting net interim earnings from gross back pay. Gross back pay is the total taxable earnings complainant would have earned during the quarter if he or she had remained in the discharging employer’s employment. Usually, the hourly wage is multiplied by the number of hours a week the complainant typically worked. If the complainant has not been reinstated, the gross pay figure should not be stated as a finite amount, but rather as x dollars per hour times x hours per week. Net interim earnings are interim earnings reduced by expenses. Interim earnings are the total taxable earnings complainant earned from interim employment (other employers). Expenses are 1) those incurred in searching for interim employment, e. g., mileage at the current IRS rate per driving mile; toll and long distance telephone call; employment agency fees, other job registration fees, meals and lodging if travel away from home; bridge and highway tolls; moving expenses, etc.; and those incurred as a condition of accepting and retaining an interim job, e.g., special tools and equipment, safety clothing, union fees, employment agency payments, mileage for any increase in commuting distance from distance traveled to the discharging employer's location, special subscriptions, mandated special training and education costs, special lodging costs, etc. Unemployment insurance is not deducted from gross back pay. Worker’s compensation is not deducted from back pay, except for the portion which compensates for lost wages.

Compensatory Damages

Compensatory damages may be awarded under all the OSHA whistleblower statutes. Compensatory damages include, but are not limited to, out-of-pocket medical expenses resulting from the cancellation of a company health insurance policy, expenses incurred in searching for a new job (see paragraph B above), vested fund or profit-sharing losses, credit card interest and other property loss resulting from missed payments, annuity losses, compensation for mental distress due to the adverse action, and out-of pocket costs of treatment by a mental health professional and medication related to that mental distress. RSOL should be consulted on computing the amount of compensation for mental distress.

Punitive Damages

Under 11(c), AHERA, ISCA, STAA,SPA, SDWA, TSCA, NTSSA, and FRSA, punitive damages are available in cases where the respondent's conduct is motivated by evil motive or intent, or when it involves reckless or callous indifference to the rights of the employee under the relevant statute.

Punitive damages are appropriate:

-

-

- when a management official involved in the adverse action knew that the adverse action violated the relevant whistleblower statute before the adverse action occurred (unless the employer had a clear-cut, enforced policy against retaliation); or

- when the respondent’s conduct is egregious, e.g. when a discharge is accompanied by previous harassment or subsequent blacklisting, when the complainant has been discharged because of his/her association with a whistleblower, when a group of whistleblowers has been discharged, when there has been a pattern or practice of retaliation in violation of the statutes OSHA enforces, when there is a policy contrary to rights protected by these statute (for example, a policy requiring safety complaints to be made to management before filing them with OSHA or restricting employee discussions with OSHA compliance officers during inspections) and the retaliation relates to this policy, when a management official commits violence against the complainant, or when the adverse action is accompanied by public humiliation, threats of violence or other retribution against the complainant, or by violence, other retribution, or threats thereof against the complainant's family, co-workers, or friends.

-

Punitive damages awards under STAA, NTSSA, SPA, FRSA, and NTSSA are subject to a statutory cap of $250,000.

5. Attorney’s Fees

In merit cases where the complainant has been represented by an attorney, OSHA must award reasonable attorney’s fees where authorized by the applicable statute(s). Attorney’s fees are authorized by all whistleblower statutes enforced by OSHA except for 11(c), AHERA, and ISCA. Complainant's attorney must be consulted to determine the hourly fee and the number of hours worked. This work would include, for example, the attorney’s preparation of the complaint filed with OSHA and the submission of information to the investigator. Most attorney fees awards, however, are determined by the ALJ and the ARB because they reflect the attorney's work in litigating the case.

6. Interest

Interest on back pay and other damages shall be computed by compounding daily the IRS interest rate for the underpayment of taxes. See 26 U.S.C. §6621 (the Federal short—term rate plus three percentage points). That underpayment rate can be determined for each quarter by visiting www.irs.gov and entering “Federal short-term rate” in the search expression. The press releases for the interest rates for each quarter will appear. The relevant rate is the one for underpayments (not large corporate underpayments). A definite amount should be computed for the time up to the date of calculation, but the findings should state that in addition interest at the IRS underpayment rate at 26 U.S.C. §6621, compounded daily, must be paid on monies owed after that date. Compound interest may be calculated in Microsoft Excel using the Future Value (FV) function.

7. Expungement of warnings, reprimands, and derogatory references resulting from the protected activity which may have been placed in the complainant’s personnel file.

8. Providing the complainant a neutral reference for potential employers.

The following table summarizes the remedies available at the OSHA investigative level under all 21 whistleblower statutes currently enforced by OSHA. This summary is provided for the convenience of the reader and should not substitute for a careful review of the statutes themselves and the applicable regulations.

J. Settlement Policy

Voluntary resolution of disputes is desirable in many whistleblower cases, and investigators are encouraged to actively assist the parties in reaching an agreement, where possible. It is OSHA policy to seek settlement of all cases determined to be meritorious prior to referring the case for litigation. Furthermore, at any point prior to the completion of the investigation, OSHA will make every effort to accommodate an early resolution of complaints in which both parties seek it. OSHA should not enter into or approve settlements which do not provide fair and equitable relief for the complainant.

Whenever possible, the parties should be encouraged to utilize OSHA’s standard settlement agreement containing all of the core elements outlined below. (See Appendix A for sample OSHA settlement agreement). This will ensure that all issues within OSHA's authority are properly addressed. The settlement must contain all of the following core elements of a settlement agreement:

-

- It must be in writing.

- It must stipulate that the employer agrees to comply with the relevant statute(s).

- It must address the alleged retaliation.

- It must specify the relief obtained.

- It must address a constructive effort to alleviate any chilling effect, where applicable, such as a posting (including electronic posting,It must address a constructive effort to alleviate any chilling effect, where applicable, such as a posting (including electronic posting.

Adherence to these core elements should not create a barrier to achieving an early resolution and adequate relief for the complainant, but according to the circumstances, concessions may sometimes be made. Exceptions to the above policy are allowable if approved in a pre-settlement discussion with the Supervisor. All pre-settlement discussions with the Supervisor must be documented in the case file.

All appropriate relief and damages to which the complainant is entitled must be documented in the file. If the settlement does not contain a make-whole remedy, the justification must be documented and the complainant's concurrence must be noted in the case file.

In instances where the employee does not return to the workplace, the settlement agreement should make an effort to address the chilling effect the adverse action may have on co-workers. Yet, posting of a settlement agreement, standard poster and/or notice to employees, while an important remedy, may also be an impediment to a settlement. Other efforts to address the chilling effect, such as company training, may be available and should be explored.

The settlement should require that a certified or cashier's check, or where installment payments are agreed to, the checks, to be made out to the complainant, but sent to OSHA. OSHA shall promptly note receipt of the checks, copy the check[s], and mail the check[s] to the complainant.

6. Much of the language of the standard agreement should generally not be altered, but certain sections may be removed to fit the circumstances of the complaint or the stage of the investigation. Those sections that can be omitted or included, with management approval include:

-

-

-

- POSTING OF NOTICE (See sample of Notice to Employees at the end of this chapter.)

- COMPLIANCE WITH NOTICE

- GENERAL POSTING

- NON-ADMISSION

- REINSTATEMENT(this section may be omitted if adequate front pay is offered)

- Respondent has offered reinstatement to the same or equivalent job, including restoration of seniority and benefits, that Complainant would have earned but for the alleged retaliation, which he has declined/accepted.

- Reinstatement is not an issue in this case. Respondent is not offering, and Complainant is not seeking, reinstatement.

-

-

In all cases other than those under OSHA 11(c), AHERA, and ISCA, the settlement must include a statement that the settlement constitutes findings and a preliminary order under [ cite the provision of the relevant whistleblower statute on findings and preliminary orders], that complainant's and respondent's approvals of the agreement constitute failures to object to the findings and the preliminary order under [cite relevant provision], and therefore the settlement is an order enforceable in an appropriate United States district court under [cite relevant provision]. In OSHA 11(c), AHERA, and ISCA cases the settlement must state that the employer's violation of any terms of the settlement will be considered to be a violation of the statute, which the Secretary may address by filing a civil action in an appropriate United States district court under the statute.

OSHA settlements should generally not be altered beyond the options outlined above. Any changes to the standard OSHA settlement agreement language, beyond the few options noted above, must be approved in a pre-settlement discussion with the Supervisor. Settlement agreements must not contain provisions that prohibit the complainant from engaging in protected activity or from working for other employers in the industry to which the employer belongs. Settlement agreements must not contain provisions which prohibit DOL’s release of the agreement to the general public.

Employer-employee disputes may also be resolved between the principals themselves, to their mutual benefit, without OSHA’s participation in settlement negotiations. Because voluntary resolution of disputes is desirable in many whistleblower cases, OSHA’s policy is to defer to adequate privately negotiated settlements. However, settlements reached between the parties must be reviewed and approved by the Supervisor to ensure that the terms of the settlement are fair, adequate, reasonable, and consistent with the purpose and intent of the relevant whistleblower statute in the public interest. Approval of the settlement demonstrates the Secretary's consent and achieves the consent of all three parties. However, OSHA’s authority over settlement agreements is limited to the statutes within its authority. Therefore, the Agency's approval only relates to the terms of the agreement pertaining to the referenced statute[s] under which the complaint was filed. If the Agency approves a settlement agreement, it constitutes the final order of the Secretary and may be enforced in an appropriate United States district court according to the provisions of OSHA’s whistleblower statutes. [4]

The approval letter must include the following statement: "The Occupational Safety and Health Administration's authority over this agreement is limited to the statutes it enforces Therefore, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration only approves the terms of the agreement pertaining to the [insert the name of the relevant OSHA whistleblower statute [s]" (the sentence may identify the specific sections or paragraph numbers of the agreement that are relevant, that is, under OSHA’s authority). These cases must be recorded in the IMIS as “Settled-Other.”

If the parties do not submit their agreement to OSHA or if OSHA does not approve the agreement signed, OSHA must deny the withdrawal, inform the parties that the investigation will proceed, and issue Secretary's Findings on the merits of the case. The findings must include the statement that the parties reached a settlement that was either not submitted for review by OSHA or not approved by OSHA.

OSHA will not approve a provision that states or implies that OSHA or DOL is party to a confidentiality agreement. OSHA will not approve a provision that prohibits, restricts, or otherwise discourages an employee from participating in protected activity in the future. Accordingly, although a complainant may waive the right to recover future or additional benefits from actions that occurred prior to the date of the settlement agreement, a complainant cannot waive the right to file a complaint based either on those actions or on future actions of the employer. When such a provision is encountered, the parties should be asked to remove it or to replace it with the following: “Nothing in this Agreement is intended to or shall prevent or interfere with Complainant's nonwaivable right to engage in any future activities protected under the whistleblower statutes administered by OSHA.” OSHA will not approve a “gag” provision that restricts the complainant’s ability to participate in investigations or testify in proceedings relating to matters that arose during his or her employment. When such a provision is encountered, the parties should be asked to remove it or to replace it with the following: “Nothing in this Agreement is intended to or must prevent, impede or interfere with Complainant's providing truthful testimony and information in the course of an investigation or proceeding authorized by law and conducted by a government agency.”

Complaints filed under STAA, ERA, EPA, A1R21, SOX, PSIA, FRSA, NTSSA, CPSIA, ACA, CFPA, SPA, SPA, or FSMA may not be settled without the consent of the complainant.

In any case under statutes other than OSHA 11(c), AHERA, and ISCA that has settled, if the employer fails to comply with the settlement, the RA or designee shall refer the case for enforcement of the order in federal district court. A letter shall be sent to the complainant informing the complainant about this referral and in cases under statutes allowing the complainant to seek enforcement of the order in federal district court the complainant shall be so advised. If an employer fails to comply with a settlement in an OSHA 11(c), AHERA, or ISCA, case, the RA or designee shall refer the case for litigation and the complainant shall be so informed.

For more information, please contact Joseph Spitzzeri, Co-Chair of Johnson & Bell's Employment group. Click here to read Mr. Spitzzeri's complete article.

___________________

Make a colleague's day: Forward this article.

[1] As of the date of this publication, OSHA’s implementing regulations for AIR21, SOX and PSIA state that complaints under those statutes must be in writing.

[2] See, e.g., Roberts v. Rivas Environmental Consultants, Inc., 96-CER-1, 1997 WL 578330, at *3 n.6 (Admin. Review Bd. Sept. 17, 1997) (complainant's oral statement to an OSHA investigator, and the subsequent preparation of an internal memorandum by that investigator summarizing the oral complaint, satisfies the “in writing” requirement of CERCLA, 42 U.S.C. § 9610(b), and the Department's accompanying regulations in 29 C.F.R. Part 24); Dartey v. Zack Co. of Chicago, No. 82ERA-2, 1983 WL 189787, at *3 n.1 (Sec’y of Labor Apr. 25, 1983) (adopting administrative law judge's findings that complainant's filing of a complaint to the wrong DOL office did not render the filing invalid and that the agency's memorandum of the complaint satisfied the "in writing" requirement of the ERA and the Department's accompanying regulations in 29 C.F.R. Part 24.

[3] Burlington Northern & Santa Fe R. R. Co. v. White, 548 U.S. 53, 68 (2006).

[4] This is true for all whistleblower statutes within OSHA's authority except for Section 11(c) of the OSH Act, AHERA, and ISCA, which provide for litigation in U.S. District Court and do not involve final orders of the Secretary.